Theodore Roosevelt’s failure to reform the English language

Some weeks back, an amusing story popped into the “Oddball” corner of the news media.  There was a small group of protesters marching and waving angry signs in front of the National Spelling Bee Championships, favoring Phoenetic Spelling.

The protesters believe English is mired by too many spellings for identical sounds and too many sounds for identical spellings. If they got their way, “you” would become “yoo,” “believe” would become “beleev” and “said” would become “sed.”

The cost of clinging to traditional spellings, they say, is millions of illiterate English speakers who struggle to read signs or get good jobs, and billions of dollars in lost productivity.

The campaign for simple spelling, which activists say started more than 100 years ago, is experiencing a revival with kids who have taken wholeheartedly to phonetic spelling in electronic messages.

Laugh all you want, but there is a tradition here. One of the big Champions of their cause was President Theodore Roosevelt. But that was part of the problem.

The Simplified Spelling Board was founded on March 11, 1906 in New York. Included among the Board’s original 26 members were such notables as author Samuel Clemens (“Mark Twain”), library organizer Melvil Dewey, U.S. Supreme Court Justice David Brewer, publisher Henry Holt, and former U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Lyman Gage. Brander Matthews, professor of dramatic literature at Columbia University, was made chairman of the Board. […]

The cause of throwing out the “gh”s in words such as “through” faltered due to the classic problems of incrementalist causes dying on the vine, and the power-fights of different branches of the government.

So as not to overwhelm the country with an entire new way of spelling at once, the Board recognized that some of these changes should be made over time. To focus their push for adaptation of new spelling rules, the Board created a list of 300 words whose spelling could be changed immediately.

The idea of simplified spelling caught on quickly, with even some schools beginning to implement the 300-word list within months of it being created. As the excitement grew around simplified spelling, one person in particular became a huge fan of the concept – President Teddy Roosevelt.

Unbeknownst to the Simplified Spelling Board, President Theodore Roosevelt sent a letter to the United States Government Printing Office on August 27, 1906. In this letter, Roosevelt ordered the Government Printing Office to use the new spellings of the 300 words detailed in the Simplified Spelling Board’s circular in all documents emanating from the executive department.

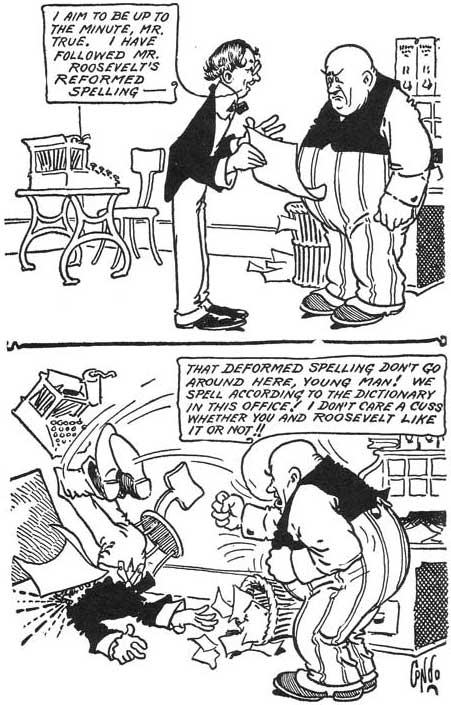

President Roosevelt’s public acceptance of simplified spelling caused a wave of reaction. Although there was public support in a few quarters, most of it was negative. Many newspapers began to ridicule the movement and lambasted the President in political cartoons. Congress was especially offended at the change, most likely because they had not been consulted. On December 13, 1906, the House of Representatives passed a resolution stating that it would use the spelling found in most dictionaries and not the new, simplified spelling in all official documents. With public sentiment against him, Roosevelt decided to rescind his order to the Government Printing Office.

Theodore Roosevelt’s Presidential Papers are full of what at first appears to be misspellings, but really are examples of his fight toward “Simplified Spelling”.

As with many a matter, I don’t quite know if Theodore Roosevelt should be considered as perpetuating Anti-Intellectualism or if he was onto something (ahead of his time in the spelling Revolution to come with the advent of text-messaging)– but maybe my equivocation is due to wanting to maintain a line of ridicule if Sarah Palin picked up on the cause. Tactically speaking, today’s incarnation of the “Simplified Spelling” cause would do well to hold an alternate Spelling Bee and see what happens.